Godzilla vs. Destoroyah 20 Years Later

(Note: This is a combination of two companion pieces, originally published on January 11th, 2016 and January 17th, 2016 in Godzilla-Movies.)

December 9th, twenty years ago, Toho released a film that marked the end of an era. Initially seen as the final Toho Godzilla entry, Godzilla vs. Destoroyah (1995) quickly became a fan favorite and is still no mere footnote—It is a pivotal transition for the franchise that many fans praise as one of the best in the series.

It's worth noting, however, that Godzilla vs. Destoroyah was never truly intended to be the final Godzilla film. Although Godzilla's “death” received stateside attention on The New York Times' front page and CNN, Toho was merely sending their Godzilla into hibernation while Hollywood produced their version. (4) "After TriStar's Godzilla is released, an entirely new Godzilla will be created by Toho," (1) said the late Koichi Kawakita, special effects director of the series from Godzilla vs. Biollante (1989) through Destoroyah.

THE BEGINNING OF THE END

Arguably the roots of Godzilla's death began during the production of Godzilla vs. SpaceGodzilla. (1994) While on-set, Godzilla suit actor Kenpachiro Satsuma suggested to Kawakita, "I think it would be good for us to stop soon.” The special effects guru agreed and felt the next production should have a larger impact on the audience. (2) Thus he decided that the “Heisei” Godzilla's life should come to an end. (8)

Producer Shogo Tomiyama wanted to kill off the Monster King through a rematch with King Kong, but Toho couldn't justify the price tag on the western beast. Instead Kong's mechanical doppelganger was considered. Mechani-Kong, from the 1967 Ishiro Honda adventure King Kong Escapes, would be “rebooted” as another G-Force mecha gimmicked with the ability to inject soldiers inside Godzilla's body. The Fantastic Voyage (1966) throwback was to pit characters against bizarre anti-bodies within Godzilla, but the concept fell through. Mechani-Kong's name and image was too closely linked to the real deal. Toho simply could not afford to pit Godzilla against his old rival. (6)

Instead Tomiyama approached Kazuki Omori to write the screenplay for Godzilla's demise. Omori had previously written and directed Godzilla vs. Biollante and Godzilla vs. King Ghidorah (1991). He also wrote the screenplay for director Takao Okawara's, Godzilla vs. Mothra (1992), the highest grossing movie in the Toho produced series up to that point and the #1 Japanese film of the domestic box office in 1993. (5) (Following Godzilla vs. Mothra's success, Okawara helmed Godzilla vs. MechaGodzilla. [1993]) For Godzilla's 1995 outing Omori came up with a story treatment remembered as Godzilla vs. Godzilla. Okawara recalled,

“Godzilla's ghost was going to appear about forty years after Godzilla was killed by the Oxygen Destroyer. The ghost gradually was going to materialize into Godzilla, and then that Godzilla was going to do battle with the [Heisei] Godzilla seen in the last few Godzilla films.” (3)

The idea was scrapped since Godzilla had fought variations of himself in the previous two films. (Godzilla vs. MechaGodzilla and Godzilla vs. SpaceGodzilla) Godzilla fighting the repeatedly scrapped Bagan was also tossed around, but it didn't get very far. (3) Instead Toho would create an all new monster that, like Godzilla vs. Godzilla, would tie into the Monster King's past.

Omori worked with Tomiyama on an early story outline; two drafts were submitted before delivering a final by the end of May, 1995. Kawakita and Okawara would contribute ideas, with the former suggesting Destoroyah should evolve through multiple forms. Meanwhile, Okawara made changes to the metropolitan police vs. Destoroyah(s) scene--Specifically, Yukari Yamane's unfortunate encounter with an “aggregate” Destoroyah. In an attempt to make the climax more “jarring” Okawara also decided to strand Miki Saegusa and Meru Ozawa at the climactic battleground near the Haneda Airport. (3)

The final battle between Godzilla and Destoroyah was supposed to take place at the 1996 World City Expo. (3) The $2.35 billion urban development project was okayed in 1990. However, Governor Yukio Aoshima pumped its breaks in late May, 1995. Refunding advanced tickets and sponsors cost Tokyo over $67 million, but it was cheaper than completing the project which had already siphoned $249 million from the city. (7)

Regardless, Toho was pressured to set the final battle at the derelict location which was even cited on-screen as "troubled". Empty buildings and unused shopping centers served as the backdrop for battles with the aggregate Destoroyahs. Godzilla's final battle was simply changed to the neighboring Haneda Airport before detouring to the district's waterfront. Somewhat callously, Tokyo used Godzilla's death as publicity for the abandoned World City Expo location. They even went as far as holding a Godzilla film festival there to promote Godzilla vs. Destoroyah. (4)(6)

On July 15, 1995, with principle photography underway, Tomiyama announced to the world that the next Godzilla film would be the last. The slew of publicity was bolstered by the less-than-subtle poster tagline, “Godzilla Dies.” (4) While Tomiyama weathered fan letters from children begging Toho not to kill Godzilla, directors Takao Okawara and Koichi Kawakita were in the middle of a rigorous schedule. (8)

THOSE WHO PLAY WITH MONSTERS

Okawara's dramatic footage was completed in almost two months with little to no improvisation. “I tried to stick to the screenplay as much as possible,” said Okawara. The director largely shot on sound stages and indoors, Omaezaki being a notable exception. (The beach where Godzilla Junior surfaces.) Additionally, Okawara was allowed to choose his own cast to play the next generation of the Yamane family. (3)

Yoko Ishino took on female lead Yukari Yamane, the niece of Emiko Yamane from Godzilla (1954). Younger sister of the popular singer Mako Ishino, Yoko also started her career in pop music. (Which lead to an odd circumstance regarding a popular arcade game based on her debut hit, Teddy Boy Blues. Ishino makes an 8-bit appearance in it.) (9)(10) Ishino began her acting career in the late 1980s, debuting with a small part in Daiei's sci-fi thriller Tokyo Blackout (1987).

Opposite of Ishino, film/television star, and wine connoisseur, Takuro Tatsumi portrayed Dr. Kensaki Ijuin--The inventor of micro-oxygen, the Oxygen Destroyer's successor. Working in television and film since the late 1980s, he recently indulged in his great passion, hosting the series Wine Romanticism. (11)(12)

Yukari's younger brother, Kenichi Yamane, is played by Yasumfumi Hayashi. Winner of the 1993 Japanese Academy Prize's Best Newcomer Award for his performance in The Rocking Horsemen (1992), Hayashi started his career with voice work in the early 1980s. (13) He continues to have a fruitful career and is a favorite of experimental film director Nobuhiko Obayashi.

Megumi Odaka returned as the “Heisei” series' telepathic, kaiju sympathizer Miki Seagusa. This would be Odaka's sixth and final Godzilla movie before pursuing a stage career cut short by deteriorating health issues. (According to Godzilla vs. King Ghidorah co-star Robert Scott Field, she is feeling better today and may return to acting in some capacity.)

Akira Nakano's Commander Takaki Aso graces the screen for a third and final time in the series. Nakano would later be seen in Godzilla x MechaGodzilla (2002) and Godzilla: Tokyo S.O.S. (2003) as Prime Minister Hayato Igarashi. He also cameos as the original “Gotengo Commander” in Godzilla: Final Wars (2004). Sayaka Osawa returns to the series as a new character, Meru Ozawa. Osawa previously appeared in Godzilla vs. Mothra and Godzilla vs. SpaceGodzilla as one of the Cosmos. She also played a minor part in Godzilla vs. MechaGodzilla.

Another notable return is Saburo Shinoda as Professor Fukazawa from Godzilla vs. Mothra. The actor has a long history of working in tokusatsu outside of his two Godzilla appearances. In Silver Kamen (1971) he played one of the title character's many brothers. He also made a small appearance in Ultraman Ace (1972) before landing the lead role in Ultraman Taro (1973).

Masahiro Takashima, winner of multiple awards for 1987's Totto Channel and Bu su, makes his second appearance in the Godzilla series. (13) Although fans know him best as Garuda pilot Kazuma Aoki (Godzilla vs. MechaGodzilla), here he plays the returning character Major Sho Kuroki. Kuroki was originally portrayed by Masahiro's younger brother, Masanobu Takashima, in Godzilla vs. Biollante. The brothers were practically born into the Godzilla series—Their father, Tadao Takashima, starred in King Kong vs. Godzilla (1962), Son of Godzilla (1967) and other tokusatsu from the Golden Age of Japanese cinema.

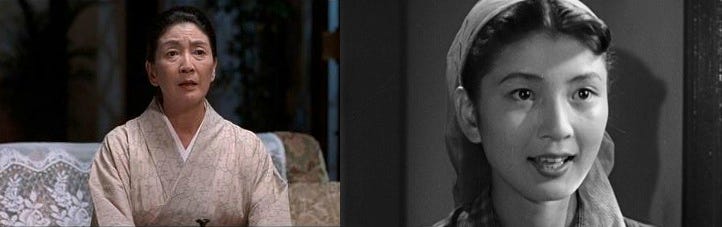

Arguably the most significant homecoming is Momoko Kochi who played Emiko Yamane in the original Godzilla. Reprising her role after forty-one years, Kochi admitted to being reluctant to return,

After the first Godzilla movie people pointed at me, saying, 'Godzilla, Godzilla.' As a young woman I hated Godzilla, so I thought, 'no more Godzilla for me.' But forty-one years later I watched the film again and realized how great it was for its anti-nuclear theme.(6)

It was Tomiyama's idea to bring Kochi back, but it was Omori who added hints of isolation to her character. "[He] came up with the idea that Emiko did not marry Ogata because she was so upset by the death of Dr. Serizawa," recalled Okawara,

I worked with her for only one day. Actors and actresses of her generation were very well trained, so I was very impressed by her. I remember that Ms. Kochi was the one who suggested that the Oxygen Destroyer be referred to not as a 'weapon', but instead as an 'invention'...(3)

MAKING MONSTERS & MELTING THEM DOWN

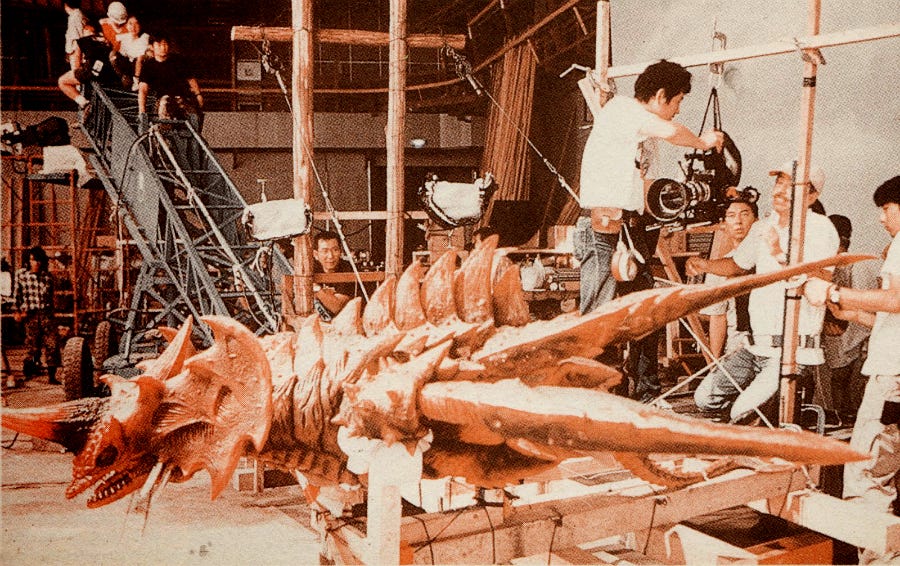

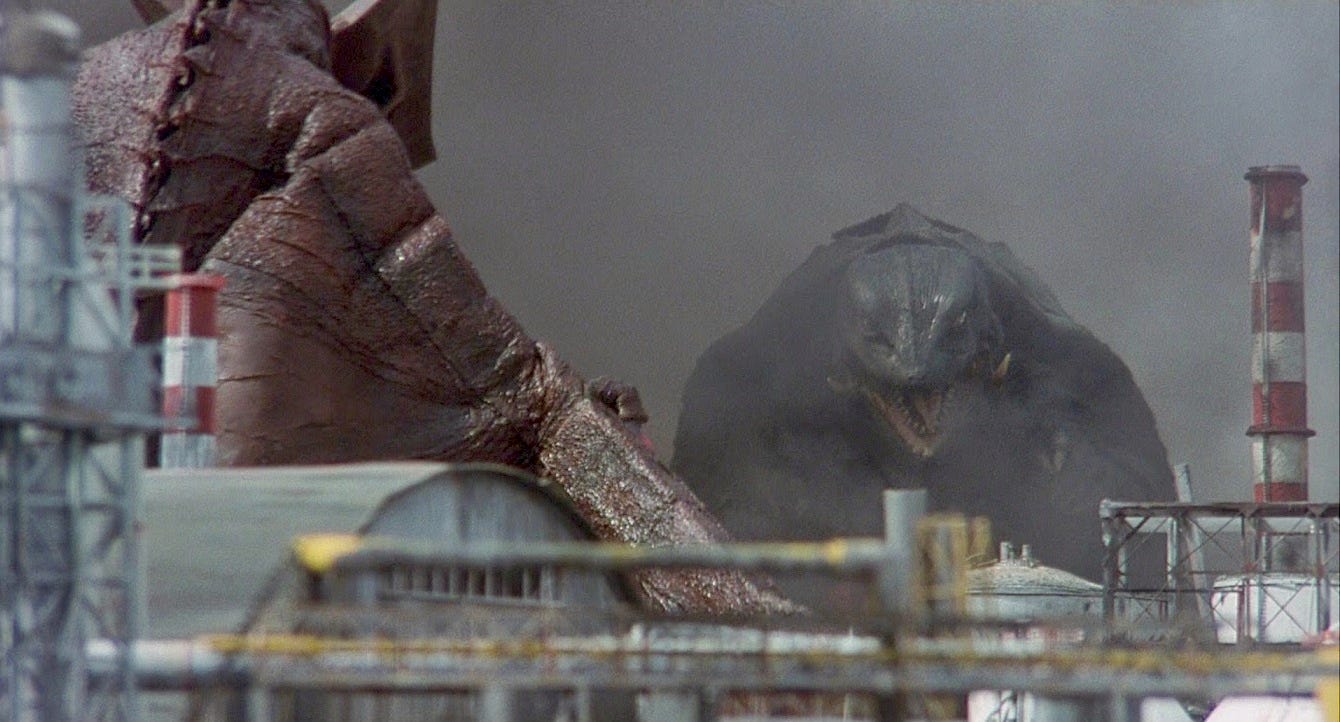

Okawara shot the dramatic footage as well as the effects heavy metropolitan police/Destoroyah confrontation. The scene has long been deemed derivative of the marine/xenomorph battle in Aliens (1986). The director admitted he was okay with the scene being evocative of James Cameron's film, believing a conflict with the aggregate Destoroyahs would remind audiences of the movie regardless. (3) Meanwhile, Kawakita and his team completed the special effects footage in three months. Nearly six weeks were used to build miniature sets and another week was spent on location in Hong Kong. “We shot during the day, but used a filter to make it seem that the footage was shot at night,” he explained. (1) The footage was used for the opening titles where a “burning” Godzilla rampages through the Pearl of the Orient.

Because the latest Godzilla series had failed to garner immediate interest overseas, Toho decided to cut Kawakita's special effects budget, leading to some peculiar innovations. Bandai Destoroyah figures were used in brief, albeit noticeable shots featuring its aggregate form. Already fighting budget cuts, theft stalled production for days. A Destoroyah and Godzilla Junior prop, "were never recovered." (1)

All of Destoroyah's forms were designed by Minoru Yoshida, infamously known for co-writing the abandoned Godzilla vs. Gigamoth project, but praised for his "Super Godzilla" design in the Super Nintendo title of the same name. Yoshida had also altered the design for SpaceGodzilla with Shinji Nishikawa. (14) The Destoroyah suit was created by Shinichi Wakasa who previously built the Rodan puppet (for Godzilla vs. MechaGodzilla) and SpaceGodzilla costume. Wakasa would best be remembered for the Godzilla suit seen in Godzilla 2000 (1999). He also worked on monsters seen in Godzilla: Final Wars, and the Mothra trilogy (1995-99). The final connection between SpaceGodzilla and Destoroyah would be stuntman Ryo Hariya, who suited up as both adversaries.

Meanwhile, Shinji Nishikawa designed the MB 96 Tank (initially conceived for the cancelled Mothra vs. Bagan) and the Super X-III. The latter was characterized as "bat-shaped", thus it was based on a Northrop "flying wing". (14) Nishikawa also returned to update his Baby Godzilla design into the pivotal Godzilla Junior. (1) The son of Godzilla would be played by Hurrican Ryu whom previously played a younger version of the character in MechaGodzilla. (Ryu also locked claws against Godzilla as King Ghidorah and Battra in Godzilla vs. King Ghidorah and Godzilla vs. Mothra, respectively.)

Kawakita had originally wanted Godzilla's entire body to glow red and white, but experiments with paint and tape came up short of expectation. Instead, the main Godzilla suit was an extensively modified version of the 1994 costume from Godzilla vs. SpaceGodzilla. Roughly two hundred orange light bulbs were placed inside the suit to make specific areas of his body glow. Transparent vinyl, molded to look like Godzilla's chest, torso, thighs and shoulders, covered the bulbs as luminescent skin. (1)

It was also Kawakita's choice to have steam coming from Godzilla. This was accomplished by pumping carbon monoxide gas out of the suit. (1) The technique proved hazardous to stunt performer Kenpachiro Satsuma, who was returning for his seventh and final outing as the King of the Monsters. “The suit only had 12 very small holes to allow me to inhale air. When they used the gas, I'd inhale that and faint,” recalls Satsuma. (4) “I fainted four times during the first day of filming … I wasn't warned about the carbon monoxide, so I wasn't wearing an oxygen mask.” (2)

Satsuma would don two separate Godzilla costumes under these conditions: The altered 1994 suit (re-christened, “Desugoji”) and a partial suit, made from the 1993 Radogoji costume, for water scenes. Additionally, an animatronic head was used for close-ups. (1)

The suit was eventually damaged by the paraffin and liquid nitrogen used to illustrate the effects of Super-X III's “freeze laser.” “We knew that it would [damage the costume],” Kawakita acknowledged, “so we shot the Super X-III vs. Godzilla sequence last.” (1)

Although Okawara claims he stuck to the script, cutting only minor bits of the dramatic footage, Kawakita had a great deal of unused special effects shots. (1)(3) Various shots of the Hong Kong attack were dropped and Destoroyah's chest beam was cut as well. Originally, Godzilla defeated Destoroyah as he was melting down, but Kawakita and his crew felt it didn't have enough impact. Thus, they shortened Destoroyah's initial death and hastily killed it off before Godzilla's demise. (1) This explains the jarring cut where Godzilla looks like he's already been hit by freezing weapons before he reaches critical mass.

The post-production process was rushed to completion in six weeks. While special effects director Koichi Kawakita worked on editing live action shots with special effects footage, the digital workload was outsourced. (1) Godzilla vs. Destoroyah featured more CGI than any Godzilla movie before it. The shots took up to a month to complete. (4) Kawakita felt the CG Oxygen Destroyer (seen in the opening credits) and Godzilla's theoretical explosion were the most difficult to nail. (1) Other notable CG sequences included Godzilla being frozen by the Super X-III and his climactic death. (4)

REQUIEM FOR A KING

One of the most revered artists in the Godzilla series, composer Akira Ifukube, would return for his eleventh Godzilla film. (Not including the stock music soundtrack for Godzilla vs. Gigan [1972].) Godzilla vs. MechaGodzilla was originally going to be his last--He passed on scoring Godzilla vs. SpaceGodzilla after reading the script, but felt Destoroyah was more his speed. "When I read the Godzilla vs. Destoroyah script I saw that it was connected thematically to the original Godzilla," Ifukube explained, feeling a sense of duty to score Godzilla's requiem. “I was involved with the birth of Godzilla 40 years before, so I felt I should be there when he dies, too.” (4)

Although Ifukube was writing themes as early as July, he didn't compose the complete score until late September and early October. After watching a rough cut the maestro had only four days to compose a full score. Recording sessions took place October 27th and 28th. (15)

Various themes from the original Godzilla would return, such as the main title march, used for Destoroyah's end credits, the Oxygen Destroyer motif and a variation of “Godzilla's Rampage”. Other returning cues included the military march from War of the Gargantuas (1966), known as 'Operation L', and King Kong's theme from King Kong vs. Godzilla (1962). (The latter was used as a bridge during the end credits march.) An original theme was composed for Destoroyah--Ifukube deliberately decided against using the original Oxygen Destroyer motif to underscore the monster. “I used the theme to help express the tragedy of Dr. Serizawa, so it wasn't appropriate for the monster,” explained Ifukube. (14) He felt the same way in relation to Godzilla's death,

“I thought of using the same motif … But I thought about the meaning of the two scenes, and I realized that a totally different type of atmosphere was needed. In the original film, Godzilla's death is the resolution of a great tragedy, and it somehow represents hope. But in Godzilla vs. Destoroyah, I believe it is more pessimistic.” (4)

The late Ifukube lamented that Godzilla's death was one of the hardest pieces of music he had composed. Starting with a modified motif written for The Big Boss (1959), the piece crescendos into a slow variation of “Godzilla's March.”

“In a way, it was as if I was composing the theme for my own death. When Godzilla was born, a phase of my life began. Now Godzilla is gone, and that phase is over. It was very emotional.” (4)

Godzilla vs. Destoroyah would be the final score of Ifukube's career. He passed away almost eleven years later, February 8th, 2006.

BOX OFFICE AFTERMATH

The film was screened for Toho executives on November 17th--By December 5th they had erected a bronze statue in Godzilla's honor. It was clear Ifukube wasn't the only one feeling emotional. Fans would visit the statue and leave offerings--10 to 100 yen coins for his passage to the afterlife. (4)(15) Four days later, December 9th, 1995, Godzilla vs. Destoroyah opened in Japan.

The film was a massive box office success. Pulling in four million attendees, Godzilla vs. Destoroyah raked in an estimated $18 million on an approximated $10 million budget. (4)(6) It was the highest grossing Japanese film for the 1996 calendar year and the most successful Godzilla movie since Godzilla vs. Mothra. (16) Toho had made a definite success of the King of the Monster's death, but it wasn't without immediate backlash. Three days after the movie opened Toho was swamped with over 10,000 letters clamoring for Godzilla's return. (4)(6) Toho responded with a wait-and-see attitude. Spokesperson Hiroshi Ono told fans, “We had to kill him. We're planning to come up with a monster better suited for the 21st century.” (4) Whether Ono was referring to the Millennium Godzilla series or not is uncertain. Regardless, Godzilla's death was slowly being ousted as a hiatus instead of an end. “As long as Godzilla is a star, he could make a comeback,” Tomiyama comforted. (6) Indeed the plan was never for a permanent retirement.

As the movie cashed in at the box office critics were less kind, largely panning the film. “Like the special effects, Omori's screenplay is a mixed bag,” wrote historian Steve Ryfle, critical of the latter half of the film. “The main characters fade into the woodwork or are reduced to mere commentators on the monster action.” (4) By contrast Shusuke Kaneko's Gamera: Guardian of the Universe (1995) had been released earlier the same year to both financial and critical success. It was so well liked that it received immediate State-side attention and distribution--Something the 1990s Godzilla films had failed to do. Gamera was hailed as one of the best in the genre, even by North American critics. (4)(6) It had become part of the reason Toho decided to hang up Godzilla's spines and tail. According to film historian David Kalat,

"Toho had been operating under the assumption that the Godzilla series had maxed out its possible Japanese audience and could only hope to maintain that level of popularity by steadily increasing the amount being spent … to 'go Hollywood' and spend even more. The inability to find a Western audience for the Heisei Godzilla movies was chalked up to cultural prejudices. And then came Gamera.” (6)

Off a $4.5 million budget (less than half of what Destoroyah was made for), Gamera: Guardian of the Universe pulled in more than $12 million at the box office. (17)(6) Meanwhile, the Godzilla movies were some of the most expensive in Japan--It was making less and less sense for Toho to be happy with $18 million when they were spending over half that amount to make movies. Additionally, Godzilla merchandise was bringing home $150 million per year. Yearly merchandise would be sustainable, making more money than a new production. (6) Add in Tomiyama's claim that Toho had “run out of ideas” and a hiatus was justified for the sake of rethinking their strategy, both creatively and financially.

THE FALLOUT & THE LEGACY

Although the film may not represent the highest quality or financial reassurance for the series, it does call back Godzilla's anti-nuclear crusade in a variety of ways. Director Okawara put it bluntly, “I want people to look at the death of Godzilla knowing that he was created by nuclear power and the most selfish existence in the world: mankind.” (4) That very power and selfishness caused Godzilla's death in 1995, the fiftieth anniversary year of Hiroshima and Nagasaki's bombing. Exhibits and historians of the time would argue over how necessary it was to use the weapon on Japan. Kalat points out the correlation with the film:

“It is no coincidence that the arguments made on behalf of the Oxygen Destroyer against Godzilla parallel the arguments made in the U.S. on behalf of using nuclear bombs in Japan. In both arguments, the awful consequences of the weapon are downplayed as a lesser human cost than if the enemy continues unchecked. In both cases, the end result is a Japanese city devastated by nuclear carnage.” (6)

Kalat also notes that advocates for the Oxygen Destroyer were heavily influenced by America: Kenichi Yamane studied at an American university and Meru Ozawa learned to hone her psychic abilities in the States. (6) Neither regret their stance, even after Godzilla's radioactive mush has contaminated Tokyo. Their attitudes aren't nefarious, merely a different point-of-view. Meanwhile, Emiko Yamane, a representation of those who lived during the war, warns her nephew about the dangers of the Oxygen Destroyer. She's one of the few still alive that witnessed its devastation up close--Her words to Kenichi mirror the arguments for the few remaining Japanese who lived through the bomb.

It is not without irony that Godzilla's end was essentially caused by nuclear proliferation. In a sense his passing could be read as Japan accepting atomic energy and ignoring the warnings he represented. By 1995 Japan had embraced nuclear power, as seen in the many recent Godzilla films—But just as Godzilla's over-absorption of atomic energy came at a high price, so did Japan's. Incidents during the 1990s left the public in a state of unease over nuclear power. On December 8th, 1995 (the day before Godzilla vs. Destoroyah opened) an event occurred at the Monju Nuclear Power Plant. Although no radiation was released, a sodium leak caused a complete reactor shut-down. The Power Reactor and Nuclear Fuel Development Corp. covered up the extent of the damage, causing outrage over how nuclear energy was being managed. (18) After a number of events, notably the Fukishima nuclear disaster, fifty of Japan's reactors were shut down in 2012. (19) As of this article, in a reverse of Godzilla's death by widespread nuclear energy, only one nuclear plant is operational in Japan and the Godzilla series is thriving at both Toho and Hollywood. (20)

Godzilla vs. Destoroyah didn't make it to North America until January 19th, 1999. Released directly to video and poorly dubbed in English, Sony Pictures Home Entertainment's version omitted the end credits, cutting the clip show of the Heisei films' better moments. (21) It was given less respect on DVD. Released January 1st, 2002, and paired with Godzilla vs. SpaceGodzilla on a flipper disc, the release was void of Japanese audio and still missing the full end credits crawl. No extras pertinent to the film were included. (22) Not until Godzilla's 60th Anniversary did Sony deliver a worthwhile edition of the film. Released on May 6th, 2014, the two disc Blu-ray set of Destoroyah and Godzilla x Megaguirus (2000) garnered better results. The film included Japanese audio, accurate subtitles (which clarified plot points for fans confused by the dub's dialog), various trailers for the film and the coveted end credits montage. (23)

Regardless of its detractors, Godzilla vs. Destoroyah is largely beloved by fans all over the world. In Japan, fans voted it the third best film in the series for Nihon's Godzilla General Election held in 2014. (24) It placed third again during Godzilla's 61st Anniversary Two Day Festival, November, 2015. (25) Although further exploitation of the series may have diminished Destoroyah's climactic impact, it is nonetheless seen as a great end to an era and a film many hold dear. The legacy of Koichi Kawakita is deeply imprinted in the production, as is Godzilla's penchant for stirring anti-nuclear dialog. The film's final shot of a resurrected, cultural metaphor, and cinematic icon, was initially seen as a fleeting moment of hope. Today it can be read as unbridled truth: Godzilla lives.

—

Citation:

1) Koichi Kawakita Interview

2) Ken Satsuma Interview

3) Takao Okawara Interview

4) Japan's Favorite Monstar – Steve Ryfle

5) Japanese Box Office Charts for 1993

6) A Critical History and Filmography of Toho's Godzilla Series – David Kalat

7) Tokyo Goveror Kills World City Project

8) Shogo Tomiyama Interview

9) Otokichi.com

10) Japanese Movie Database

11) Tatsumi's Wine Romanticism

12) Destination NSW

13) Celebs by New Comer of the Year

14) Shinji Nishikawa Interview

15) Akira Ifukube Interview

16) Japanese Box Office Charts for 1996

17) Toho Kingdom

18) Reactor Accident in Japan Imperils Energy Program

19) Japan Shuts Down Last Working Reactor

20) Four Years After Fukushima Japan Makes a Return to Nuclear Power

21) Godzilla vs. Destoroyah VHS

22) Godzilla vs. SpaceGodzilla/Godzilla vs. Destoroyah Double Feature DVD

23) Godzilla vs. Destoroyah/Godzilla x Megaguirus Blu-ray

24) Japanese Fans Pick Godzilla vs. Biollante...

25) Ranking of Godzilla Films from Godzilla's 61st...